Happy new tax year?

The start of the new tax year brings with it one of Rishi Sunak’s major tax reforms: the rise in National Insurance, announced last September and linked to additional support for the NHS and social care. This spotlight explores what this rate rise – together with freezes in the Income Tax personal allowance, the newly-announced National Insurance threshold rise due in July, and an Income Tax rate cut due in 2024-25 – will mean for workers, households, the tax system and the public finances.

What changes are happening?

The new fiscal year 2022-23 brings a number of immediate changes that will affect household incomes. Most benefits are rising by (only) 3.1 per cent; the National Living Wage is rising by 6.6 per cent to £9.50 an hour; and the energy price cap is rising by 54 per cent. Around four in every five households are due to receive a £150 rebate in April through the Council Tax system (although English Council Tax bills will also rise by an average of 3.4 per cent); a 5p Fuel Duty cut has already taken effect; and VAT on hospitality has now returned to its pre-pandemic rate of 20 per cent. But there are also a number of changes occurring in the direct tax system:

- The four-year freezing of Income Tax thresholds begins (alongside a freezing of Inheritance Tax, Capital Gains Tax and VAT thresholds). This will not mean a nominal jump in anyone’s tax bills, but means that the personal allowance will remain at £12,570 rather than rising (by the 3.1 per cent that it would have done had the Treasury followed its usual rules) to £12,960, and the higher-rate threshold will remain at £50,270.

- Tax rates for dividend income are rising by 1.25 percentage points, as part of the ‘Health and Social Care Levy’ package. This only affects people with over £2,000 of dividend income – not including anything received within ISAs or pensions – and raises only around £600 million a year, and so is not a focus of this spotlight.

- Most significantly, all National Insurance (NI) rates will rise by 1.25 percentage points in April (ahead of the true ‘Health and Social Care Levy’ being introduced in April 2023). This effects employers, employees and the self-employed, and means that the basic NI rate for employees will rise from 12 per cent to 13.25 per cent.

- Working in the opposite direction, however, the starting point for paying non-employer NI is rising in April from an annual equivalent of £9,568 to £9,880 – in line with the rate of inflation last autumn – but will then, as announced in the Spring Statement, jump to £12,570 in July.

What effect will 2022’s National Insurance and Income Tax changes have on people?

The overall impact of these policy choices on people’s incomes will be complex, as changes in allowances and thresholds interact in complicated ways with changes in rates. However, in isolation they are more straightforward. We can characterise their effects as follows:

- The freezing of the Income Tax personal allowance will leave (almost all of) the 33 million people who pay Income Tax each year around £80 worse off compared to a world where the Chancellor had followed the usual rules for uprating it (as well as bring around 400,000 extra people into Income Tax), and the freezing of the higher-rate threshold will leave higher (and additional) rate payers an extra £160 worse off.

- The personal NI rate rise will only affect earnings but, as an extra 1.25 per cent tax on annual earnings above £9,880 (in April), it will mean additional tax of around £200 a year for someone earning £27,000, and around £1,100 for someone earning £100,000.

- The significant increase in the NI threshold will mean a tax cut of £270 across 2022-23 (accounting for the fact that it does not take effect until July) for employees earning above the new threshold, and will also take around 2 million workers out of direct tax altogether.

- Those affected by these changes and also receiving Universal Credit (UC) will only get 45 per cent of any tax cut (or pay 45 per cent of any tax rise), as the benefit is tapered against net earnings, so higher net earnings lead to a reduced UC award.

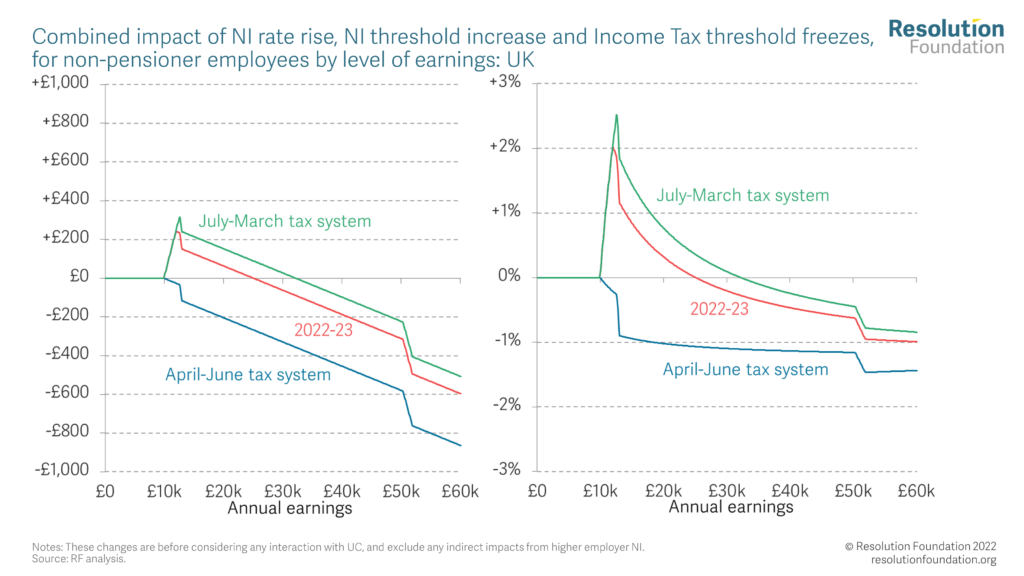

Figure 1 shows the combined impact of the three big changes for employees (ignoring the interaction with UC, and excluding any impacts from increases in employer NI – although we discuss that further below). In the period from 6 April to 5 July, workers will clearly be worse off, with most losing around 1 per cent of their gross pay to higher NI and Income Tax (relative to a world where none of these changes was made). But when the starting point for NI increases in July, everyone earning less than £32,000 a year will be better off from the combination of these policies. In absolute and proportional terms, the biggest winners will be those with earnings near £12,570 a year (note that those earning below £9,880 will be unaffected by any of these changes).

Figure 1: In 2022, the increase in the National Insurance threshold will more than offset other tax rises for many workers

Looking over 2022-23 as a whole, those employees (below State Pension Age) earning between £9,880 and £25,000 – around 1-in-3, or 9 million employees – will pay less tax overall from the policy changes, with around 15 million worse-off. Among the self-employed (who pay a lower rate of NI and therefore benefit less from the threshold increase), those earning below £20,000 will be better off.

Given that the median retiree income is around £12,000, the majority pay no Income Tax and are therefore unaffected by the personal allowance freeze, at least for now (note that pensioners’ household incomes after housing costs are no lower than the rest of the population’s, despite these low individual incomes).

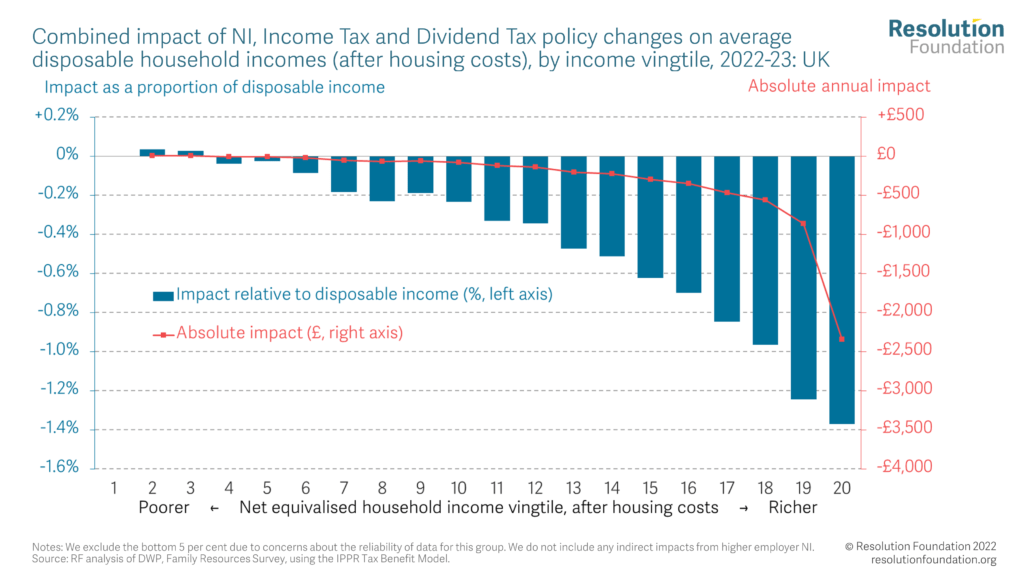

Moving from individual to household-level incomes – in Figure 2 – also shows a progressive pattern for 2022-23’s personal tax changes, with negligible or even positive average impacts on lower-income households, and the greatest impacts (both in absolute and relative terms) for the highest-income households.

Figure 2: The total effect of personal tax changes in 2022-23 will be progressive

What effect will the changes have on the tax system?

The most significant impacts of these changes will undoubtedly be the direct effects on household incomes and on the funding of public services, but the impacts on the tax system and its incentives should also be considered. A higher NI threshold will reduce participation tax rates, increasing the incentive to start or remain in work, while higher NI rates will reduce the incentive to earn extra, though these are no doubt small effects.

It is welcome that the starting points for Income Tax and personal (but not employer) NI will now be aligned, at £12,570 (this will also be the starting point for the Health and Social Care Levy from April 2023). One difference between these thresholds, however, is that NI operates on a per job basis – whereas Income Tax is based on total income – and therefore people with two jobs get double the benefit from the threshold rise, so April’s changes slightly increase the incentive to have multiple jobs.

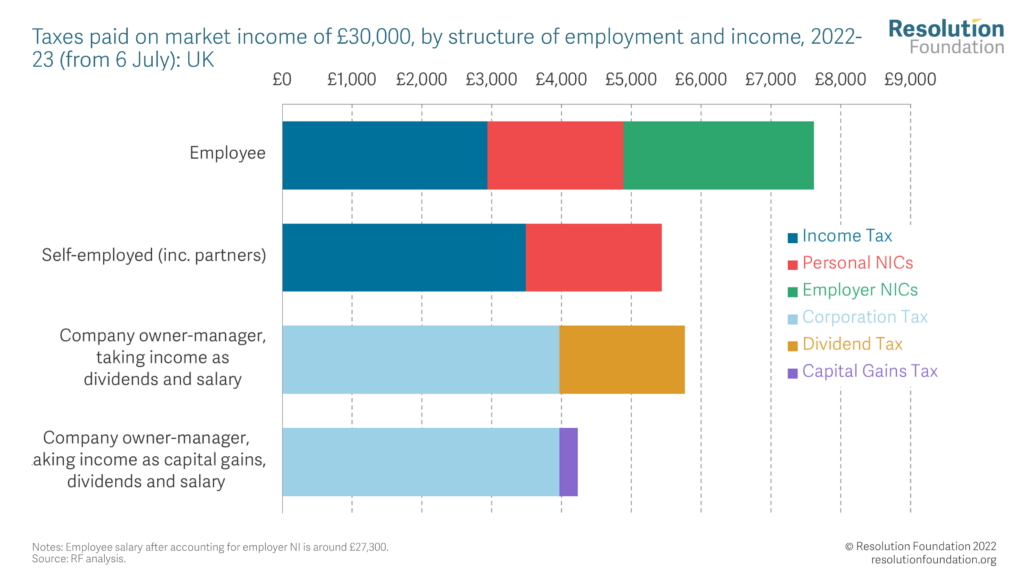

A more important area of concern is that increasing employer NI worsens the tax system’s bias against employment. Following the April 2022 changes, a market income of £30,000 would attract over £2,000 less tax if structured as self-employment rather than employment – as illustrated in Figure 3 – and there are even lower-tax possibilities via incorporation.

Figure 3: Increasing employer National Insurance exacerbates the tax system’s bias against employees

So far, we have ignored the impact of the rise in employer NI. In the long-run, much of the rise in employer NI will be passed on to employees in the form of lower pre-tax wages. The OBR estimate that April’s increase in employer NI will leave nominal earnings 0.5 per cent lower and prices 0.1 per cent higher than they would otherwise have been (though a small fraction of this may be offset by the increase in employers’ Employment Allowance that was announced in the Spring Statement).

What effect will the changes have on tax receipts, and what is still to come?

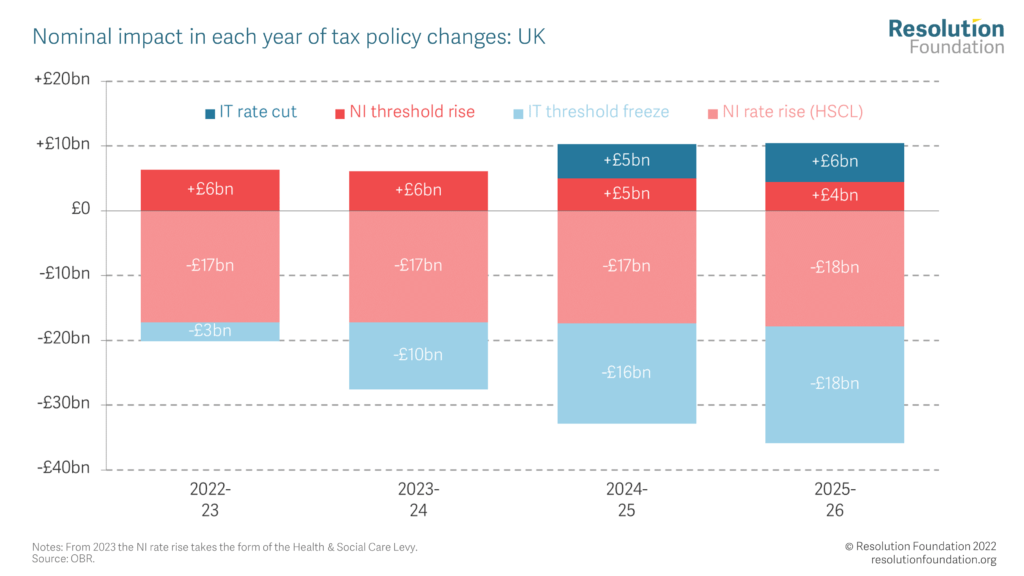

Figure 4 sets out how much revenue these tax changes are expected to raise – or lose – in 2022-23 and beyond. This year’s Income Tax threshold freezes will raise around £3 billion a year for the Treasury, but it is the April 2023 freeze that will doubtless be more significant, given that, under the current forecast for inflation this autumn, these would ordinarily rise by around 7.5 per cent. The fact that inflation is currently forecast for be much higher than when the policy was announced means that, while the four-year freeze was originally forecast (in 2021) to raise £8 billion in 2025-26, it is now forecast to raise £18 billion. One could argue that some of this revenue windfall has been redirected to cutting the basic rate of Income Tax, which the Chancellor has announced will fall from 20 per cent to 19 per cent in April 2024, at a cost of around £6 billion a year.

The NI rate rise this year is expected to raise around £17 billion (although some of this is offset by extra funding provided to government departments to cover their own tax increases, and the yield is also impacted by the assumption that the rise in employer NI will suppress wages, which has fiscal implications). Raising the NI threshold will cost £6 billion in 2022-23, but this cost reduces over time as the threshold will be frozen until April 2026.

Figure 4: Beyond 2022-23, the most significant personal tax changes are expected to be the continued threshold freezes and the cut to the basic rate of Income Tax

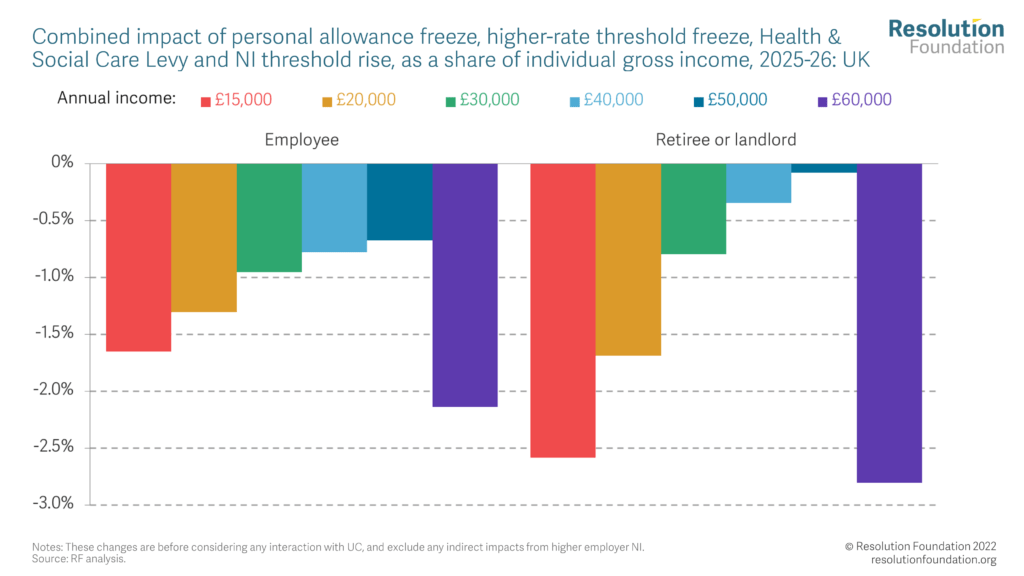

Thinking about all these tax changes together, almost all direct taxpayers will pay higher taxes in 2025-26 – with the exception being a small group of workers (with earnings of around £11,000 to 13,000) who earn enough to benefit from the raised NI threshold but not enough for that to be offset by the personal allowance freeze. The net impact on different groups will vary enormously, however.

Looking first at retirees (or others whose income is not liable for NI), high inflation means that the four-year personal allowance freeze is now projected to cost them around £400 in 2025-26. For a retiree with an income of £50,000, this is largely offset by the basic rate cut (worth £370 for them), but for someone on £15,000 this only provides a £20 offset, leading to a regressive pattern, with the former losing only 0.1 per cent of their income but the latter losing 2.6 per cent (as shown in Figure 5). Higher-rate taxpayers, however, are additionally hit by the higher-rate threshold freeze.

The picture is broadly similar for employees, despite the progressive combination of the NI threshold rise and NI rate rise. The net tax rise in 2025-26 is projected to be 1.7 per cent for an employee on £15,000, but only 0.7 per cent for someone on £50,000.

Figure 5: The confusing combination of income-related tax changes creates inequities between income groups and between sources of income

In terms of the overall household income distribution, the package of tax changes is still progressive (most tax rises are). But it is hard to imagine that the pattern shown in Figure 4 is a deliberate, optimal outcome. In the Spring Statement, rather than cutting the basic rate of tax, the Chancellor could have announced – for the same cost – that the starting point for tax would not be frozen at £12,570 in 2024-25 and 2025-26, but would instead rise with inflation to £13,200. This may not have been as memorable as a rate cut, but it would have avoided this regressive pattern, and would have been a better deal for employees earning below £34,000 and retirees with incomes below £26,000. As it stands, there is set to be both an Income Tax rise and Income Tax cut in 2024-25, and a further tax rise in 2025-26, with a net transfer from lower- to higher-income individuals.

For now though, it is the NI rate rise and (from July) the subsequent NI threshold rise that will have the biggest impact on workers’ pay checks, alongside the even more significant impact of very high inflation on real incomes. As others at Resolution Foundation have noted: “promising a tax cut tomorrow, while allowing benefits to fall today as prices soar just isn’t serious policy making”.