It’s all about the wages, stupid

Yesterday’s good news: the reason the Bank of England increased interest rates is because it thinks the growth in your pay packet is about to start picking up. The bad news: it doesn’t think they’re going to pick up very far because we’re just not very good as a country at improving how we produce things. That’s the summary of what we heard from Mark Carney and (most of) his colleagues yesterday. Whether they are right is much more important for our living standards than the actual increase in rates itself.

The Bank has come to a different view on the case for raising rates now to most external economists and commentators. However they do agree with their critics that the path of wages, as the central determinant of domestic inflation, is key for deciding when a rate rise should take place. It is all about wages. So what’s going on with our pay packets, and why is the Bank seeing signs of pay rises many people don’t feel?

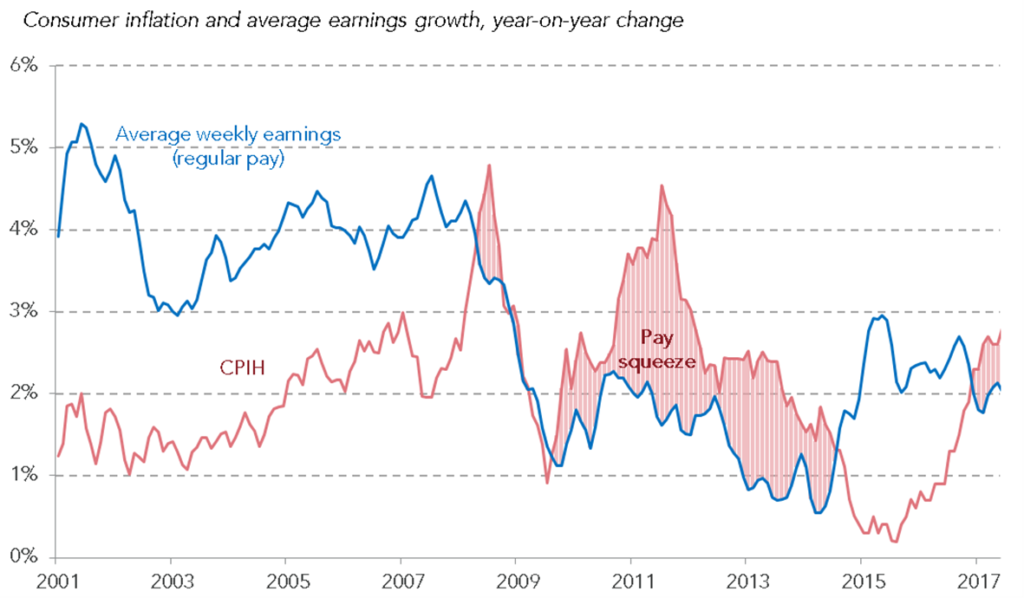

The first simple fact – more or less the only fact that the Bank’s critics think they need – is that real wages have spent 2017 actually falling.

You can pass the blame for falling real wages onto temporary higher inflation. But the growth in nominal wages is also historically low – hovering above 2 per cent, compared to an average of 4 per cent pre-crisis. It hasn’t been boom time Britain for workers over the past year.

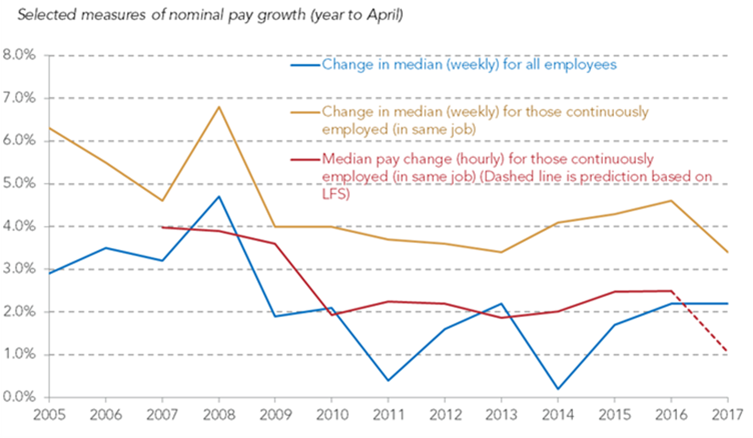

But what does looking beneath those headlines tell us? In the past some have argued that yes overall earnings measures might be growing slowly (the blue line below) – but that hides stronger wage growth for the typical worker who stays working in the same job from one year to the next (the orange line), as the majority of us do. Focusing on the latter is more important, the argument goes, because it removes the effects of new people coming into and others leaving employment and provides a purer measure of wage pressure. This used to be a favourite argument of George Osborne (as Chancellor, not newspaper editor).

This is a bad argument in the context of the Bank’s task of examining whether wage pressures risk feeding through to faster price rises. Firstly that’s because, even on this alternative measure of earnings growth, wage rises are far below pre-crisis norms. Secondly, if anything they have declined faster than overall average wage growth recently. And thirdly (but most importantly), if you’re looking for some form of the going rate for those staying put, it’s the typical wage rise (the red line above) that matters rather than the wage rise of the typical worker. On that measure there is no grounds for coming to a different conclusion about whether wage growth has taken off. In fact our estimate is that it has fallen further in the most recent data (for the year to April 2017).

There are however two better arguments, for those wanting to see emerging signs of wage pressure.

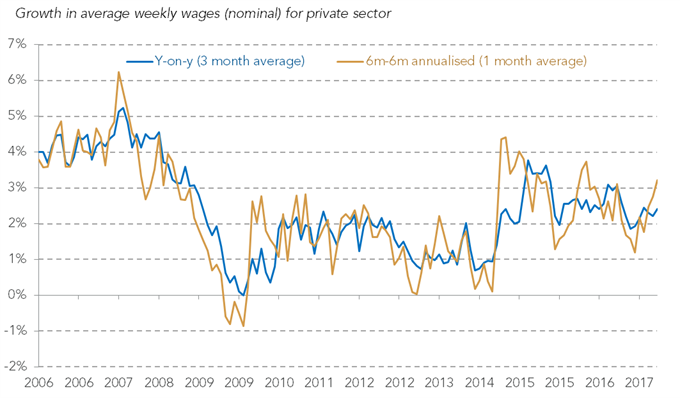

First, while annual wage rises on the main data sources show no sign of an uptick, there are signs of a more recent pick up in the private sector. In the six months to August, private sector wage growth reached an annualized equivalent of 3.2 per cent (see the orange line below). The optimists reading is that with unemployment falling to a 42-year low and, as we’ve previously shown, that tightening feeding into upward pressure on job quality (such as the fall in zero hours contracts and switch to full time employee jobs), pressure on wages is next in line.

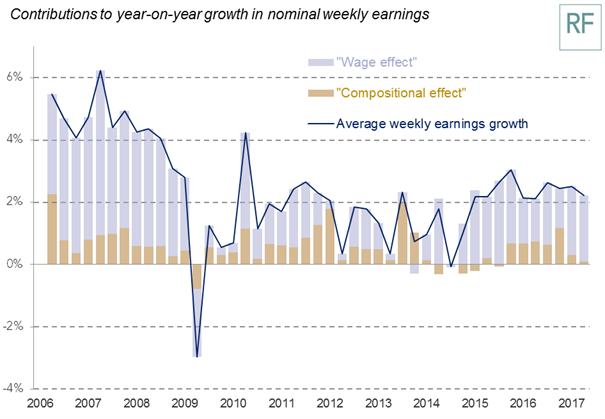

Second, they might say (indeed Mark Carney argued exactly this yesterday) that wage pressure is being understated because of a short-term weakening of normal upward pressure from the improving nature of the workforce (e.g. becoming more qualified over time) and the work being done (e.g. the longer term trend into higher paying occupations). This so called “compositional” boost to earnings is expected to restart soon so, the Bank argues, underlying wage pressure is higher than the headline figures suggest. As the chart below shows there is something in this argument – the pure wage effect has not fallen as far as the headline average earnings growth figures imply.

These are not ridiculous arguments, and both short-term movements and the impact of compositional changes are things we should be looking at when trying to decide if the labour market is at a turning point for wage growth. But as of today they are a long way from conclusive. A few months of faster private sector wage growth does not prove we’ve decisively turned a corner – indeed we saw a similar spike up in wage growth in 2015 that turned out to be short lived. As the dissenting voices on the Monetary Policy Committee pointed out, it is just too early to tell whether a corner has been turned. Let’s hope it has, given that what we definitely do know about wages is that we’re starting from a very bad place.

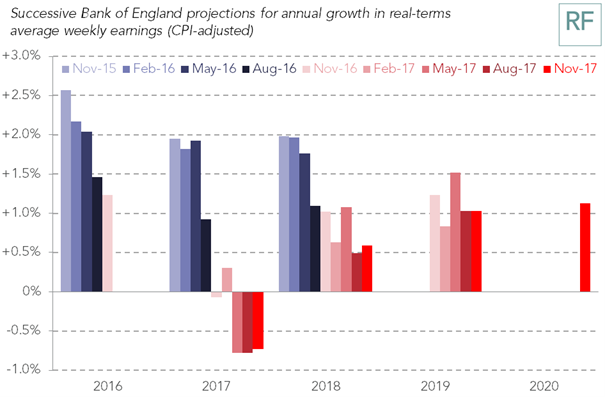

But while on short-term pay the Bank are looking chipper, their longer term outlook for our pay packets is anything but. Their pessimistic view on the capacity of our economy to grow, with slower productivity growth than we previously thought Britain was capable of, feeds through into us being a country where the norm is for smaller pay rises. They are forecasting real wage growth never getting above 1.2 per cent in the coming years, less than half the pre-crisis norm.

So what can we say for sure on wages? Firstly, the big picture is of a wage disaster, with average earnings still £15 a week below their pre-crisis peak. Secondly, the last year hasn’t been great with higher inflation leading to a return of the pay squeeze. Thirdly, there is some evidence of faster private sector wage growth more recently – but it really is just a few months’ data.

Let’s hope the Bank is right that it heralds the return of wage pressure. And hope they are very wrong on low wage growth for years to come.