Brooding over beer and crunching the cricket numbers

Afternoon all,

I’m all for some routine in life. It helps contain the existential angst. So at least the Bank of England is helping with their now traditional monthly interest rate rise. Obviously that’s less useful on the financial angst front, but you can’t have it all.

I’m down in Dorset today and didn’t see any signs of blind panic on the streets of Swanage this morning. But then again half the county owns their homes outright so this isn’t the homeland of the mullered mortgagors. That’s mid-Bedfordshire where 41 per cent of voters in the upcoming by election have a mortgage…

The government knew the rate rise news might push us to do something stupid like drink heavily this weekend – so they (rightly) whacked up alcohol duty on Tuesday. COTW has some British booze background, while our reads this week provide you with healthier stimulation options.

I’m shortly off for an unimaginative/badly needed few weeks in the Alps so TOTCs will be having its summer break – back on the 1st September. I’d like to think not, but I reckon you’ll cope.

Have a fun August.

Torsten

Pondering policy. You want two words to rile up a room full of economists (or indeed the Economist)? Industrial. Policy. A considered version of the pro side of the argument comes in a new paper from Dani Rodrik and colleagues, that reviews the recent literature and poses policy questions. Their starting point: despite what some economists might like, and what some politicians say, industrial policy is something governments do so let’s focus on doing it well. Second, that the literature shows it can work. Especially if your definition of “work” is influencing employment in certain industries and places. The most interesting bits relate to the nature of industrial policy itself. The traditional view is of subsidies or trade protection to support manufacturing, but the authors say policy makers should focus on providing firm/sector specific inputs (think training/infrastructure) and recognising that if industrial policy is about more good jobs in more places then we’ll have to figure out how to effectively support services. We’ll get into that and more on Wednesday 27 September when Dani is giving a lecture at Resolution for the Economy 2030 Inquiry. Come along.

Charting cricket. TOTCs does charts, not cricket. But it’ll obviously be awkward this weekend not having any chat about the Ashes. So for any of you in the same boat, here’s a data led read on whether England’s new energetic/freewheeling “Bazball” style of play (ludicrous name comes from England coach Brendon “Baz” McCullum) is really any different to what came before. The author does some stats to show that this attacking form of cricket is producing very unusually high run rates (on their measure it’s seen 8 of the top 30 most surprisingly high run rates this century in basically just a year). At least I think that’s what it says – I may have the wrong end of the stick wicket.

Political promotion. Bazball is high risk/high reward and so is… politics. Obviously that’s true for politicians and their close aides, whose jobs directly depend on the outcome of an election. But it’s also true for the lowly workers who make campaigns happen on the ground. So we learn from a study of workers on Brazilian mayoral campaigns, which shows that those working for winning rather than losing campaigns are working and earning more in the post-election years (earning 10 per cent more four years on). Lots of this boost comes from significantly increasing the chance someone is working in the formal labour market (a big deal in Brazil) – specifically by being 55 per cent more likely to be in a public sector job. The authors see this less as outright corruption (the effect is strongest for high ability/qualified workers) and more that being a campaign worker helps younger workers overcome the barrier of lacking formal labour market experience and networks. So you youth should get involved in politics. Just make sure you pick the winning team.

Wages where? Another big paper on the economic gaps between places debate came out this week, with it’s USP being a detailed comparison of developments across Canada/France/Germany/UK/US over 50 years. There’s a lot to dig into. One of the authors laid out the UK headlines on twitter whatever it’s called these days. Their (controversial) findings are that wage gaps between places in UK are high, but not exceptionally so (US far higher), and have been flat/falling this century (all the damage was done in 80s and 90s). How do we reconcile this with the sense that gaps have got bigger? Because while wage gaps may have come down (hello the minimum wage), income gaps haven’t done so (as we’ve shown before capital and self-employment income has become more concentrated in rich places this century). Anyway the paper should encourage us to 1) focus on these regional gaps because they are simply so much bigger post-deindustrialisation and 2) (horror!) look at France which has bucked the trend for wage gaps to grow (note mainly via having few high earners).

Promoting paternity (leave). The UK’s gender pay gap has come down, in large part as women’s educational outcomes and labour market participation has soared in recent decades. But a big gap persists, that is almost entirely due to parenthood – specifcally the different impact it has on mothers (terrible) and fathers’ (not much) careers. How do we get more progress? Changing social norms around care giving. A new paper, examining the 2007 modest rise in paternity leave (a whole extra 13 days on top of the existing 2!) in Spain finds it didn’t just have the desired short term effect (men being at home more when their children are very young) but had lasting impacts on the next generation. Children born after the policy change are more egalitarian/less likely to believe to stereotypical social norms of earlier generations. Social change – it’s a long game but policy can make a difference.

Chart of the week.

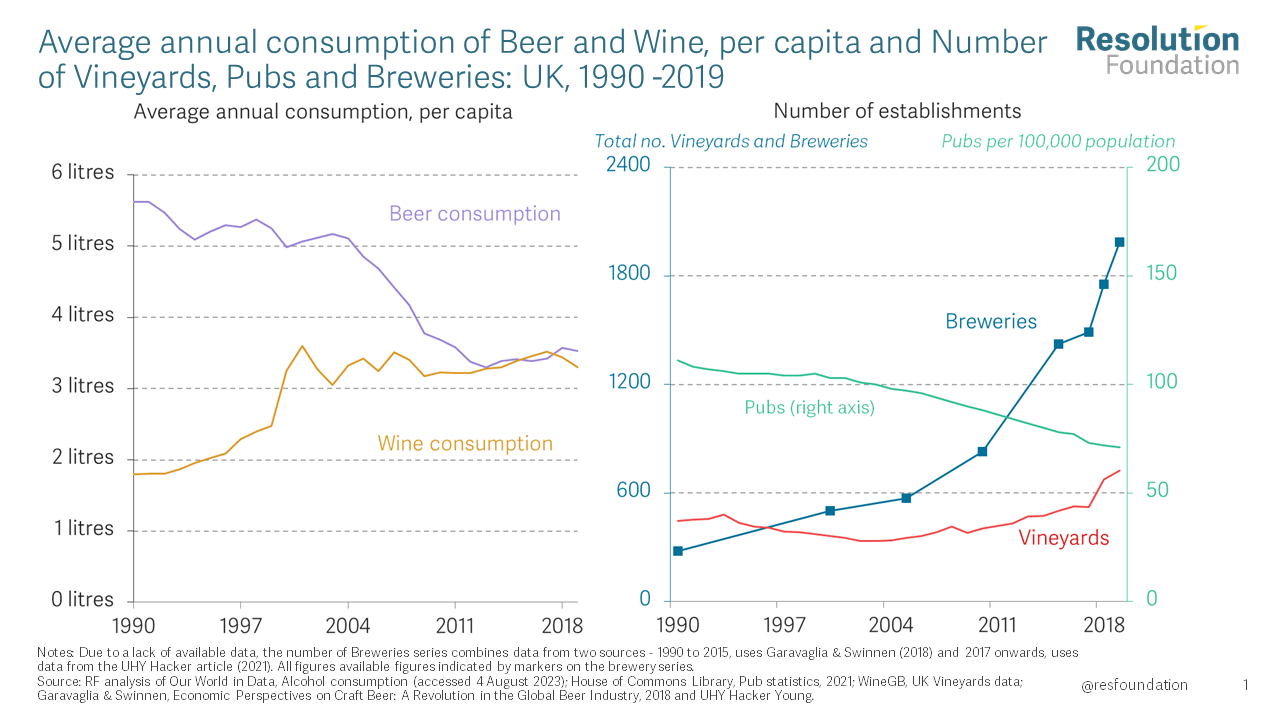

It wasn’t just rates that went up this week. So did alcohol duty, after a long period of freezes since 2020. This is an inflation rise plus the system has been moved towards taxing more by strength rather than volume (a good idea). A bottle of wine will now set you back an additional 53p, while a pint of beer will have its duty cut by 11p. This is an excuse for a COTW on the state of British booze. Obviously you’ll know all the pubs are closing. And you’re partly to blame, given chunky falls in beer drinking. But it’s not all bad news for alcoholics booze enthusiasts. We’re drinking loads more wine. Luckily this isn’t just swelling the coffers of French chateau owners, we’re seeing vineyards popping up all over the place. Those of you filled with terror at visions of a berets/baguettes/Burgundy filled Britain should chillax: brewery numbers are surging too. We do still like our beer, but we’d like it craft, thanks.