Apprenticeships system favours those who already hold skills

This morning the Department for Education (DfE) published figures outlining the number and type of apprenticeships that were started during the first month of 2019. January isn’t a big month for apprenticeship starts. However, it does mark the completion of the first half of the academic year and, as such, is a good time to take stock of how today’s system compares against the recent past.

So first, the numbers. Provisional figures tell us that 29,100 people began an apprenticeship during January 2019 and 226,000 began one between August 2018 and January 2019 (the first half of the 2018-19 academic year).

A continuing pattern

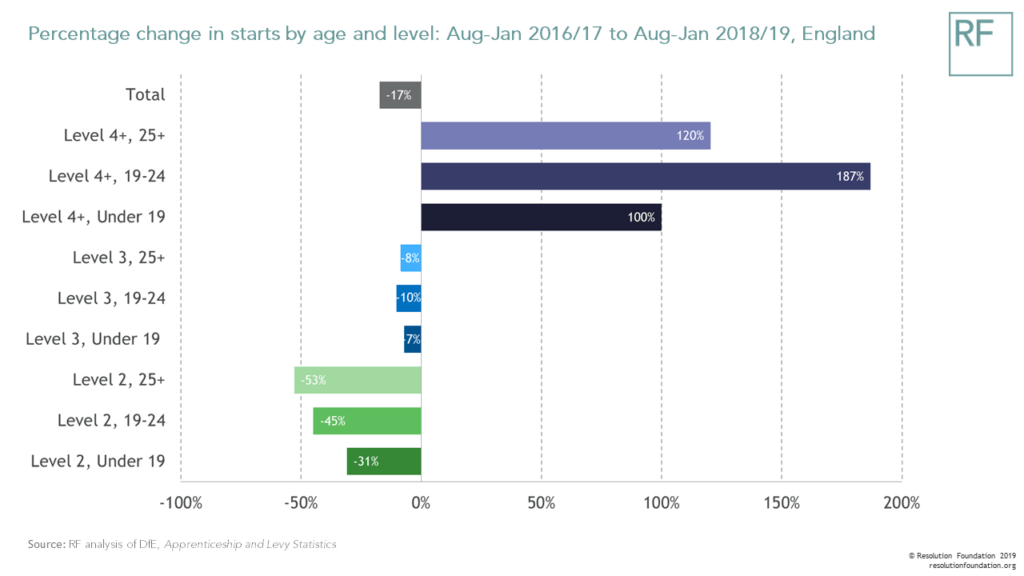

Figure 1 shows that the total number of starts (so far) this academic year is 17 per cent down on the same period in 2016-17 (final figures, and before the levy was in operation) and just 4 per cent up on the same time last year (after the levy was in place). In other words, the initial post-levy fall in starts has stabilised; we are now operating in a system that offers fewer apprenticeships than in the past.

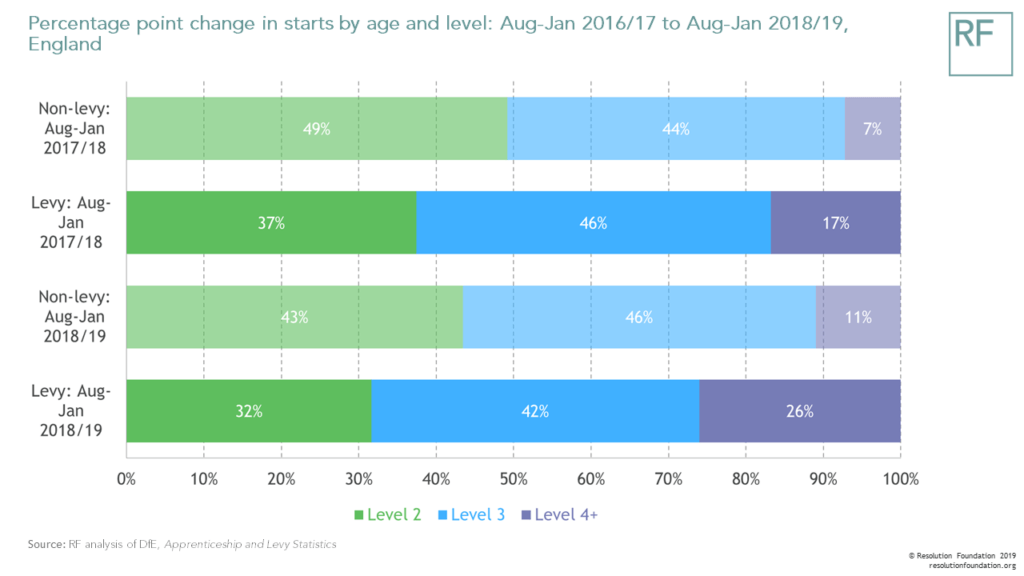

Of course, much of the narrative around the apprenticeships system has shifted away from the headline numbers and towards its composition of starts. Even ministers appear to be playing down the likelihood of hitting that 3 million starts by 2020 target. And it’s in the composition of courses where we see substantial change. As the chart below shows, the number of level 2 apprenticeship starts has broadly halved between the first half of 2016-17 and the first half of 2018-19. In contrast, the number of level 4 starts has more than doubled (albeit from a lower base).

On the one hand, we shouldn’t worry much about the declining number of level 2 apprentices over the age of 25. After all, last year we at Resolution Foundation reported on apprenticeship evaluation figures that showed more than half (55 per cent) of people on these courses were unaware that they were even an apprentice.

Moreover, the 2016 apprentice pay survey found that almost one-in-three apprentices aged 25 and over in their second year were paid less than the legal minimum. In a world where we want to raise the profile and stature of vocational education, these kind of courses risk causing major damage to the apprenticeship brand.

Skills gap

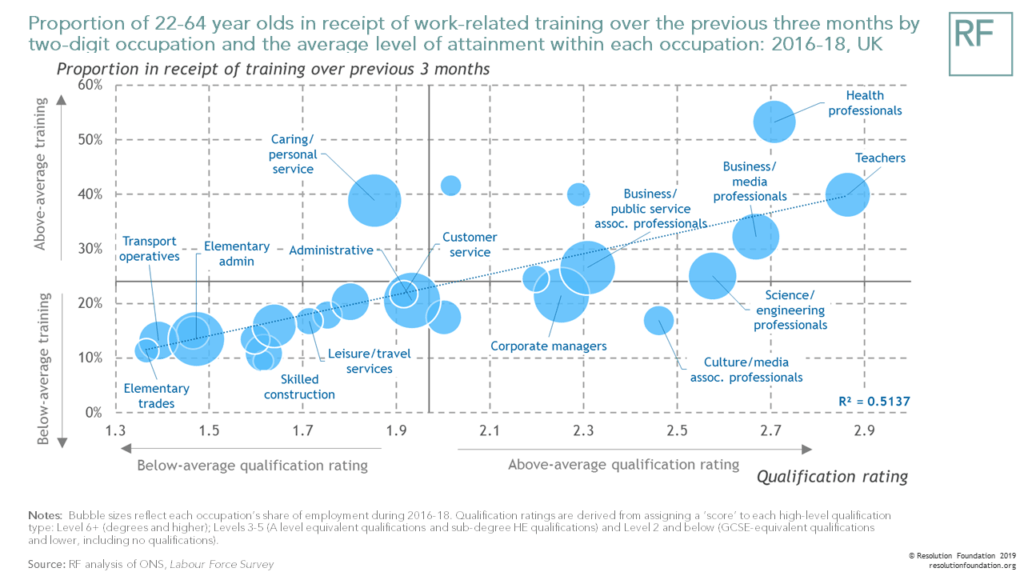

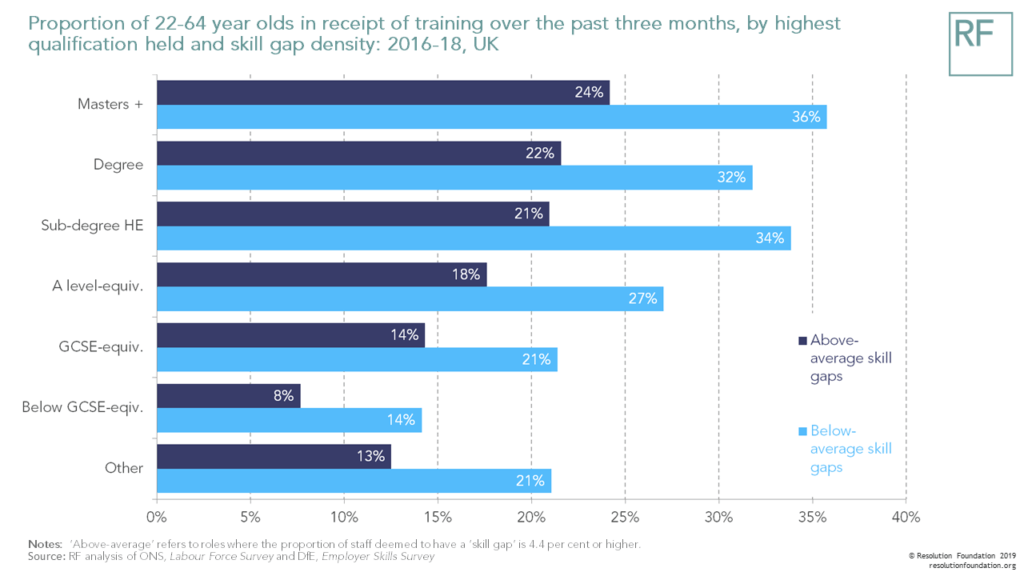

On the other hand, recent Resolution Foundation research has found that workers with lower-level qualifications, and/or who work in lower-skilled occupations receive less frequent training than their counterparts who either have higher-level qualifications or work in higher-skilled occupations. This is a skills gap that needs filling (as figure 3 below shows) – and level 2-3 apprenticeships could have an important role to play in this.

We know that this is a problem for firms, who often complain about workers’ competencies. In 2017 they stated that 4.4 per cent of UK staff lack the skills to be fully proficient in their job, with these “skill gaps” tending to be concentrated in lower-skilled roles. Yet despite their complaints, firms are exacerbating this problem by offering less frequent training to employees in roles that are said to suffer from an above-average level of skill gaps.

Poor quality apprenticeships

So, while we can welcome the drop off in poor quality apprenticeships, we’re also right to worry that today’s apprenticeships system risks reinforcing a longstanding pattern in which training and development is (disproportionately) directed towards the “already-haves”. We shouldn’t be surprised by this either.

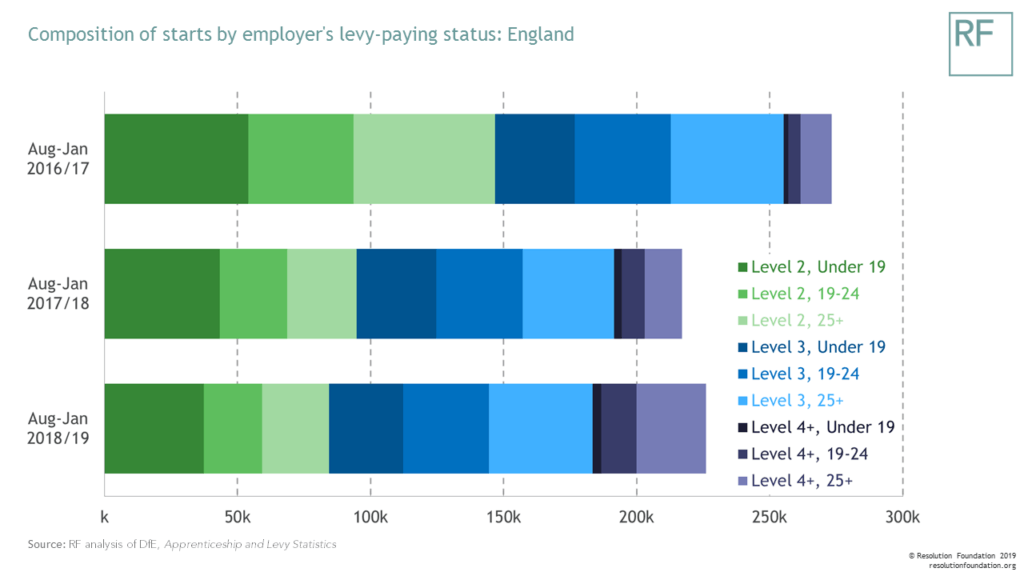

After all, the apprenticeships system is “employer-led” and the apprenticeship levy, by its very nature, is paid by large employers – many of whom are likely to be staffed by already-highly-qualified workers. A quick glance at figure 5 helps to illustrate levy payers’ (relatively stronger) tendency to focus on apprenticeships at higher levels.

Over the coming months, the Resolution Foundation will be digging further into the mechanics of this. We’ll be looking at how the composition of starts differs by levy-payer status and industry, and what this means for the number and type of opportunities for future learners.