Strictly Come Building: How housing can make a star turn in the upcoming Budget

Lowering expectations ahead of a Budget always helps a Chancellor. And when it comes to expectations of Cabinet members, Boris Johnson and Priti Patel have definitely been in the lowering business. But others have made the Chancellor’s task harder rather than easier. Robert Chote, the chair of the Office for Budget Responsibility, is set to nudge his forecasts in a pessimistic direction. The Prime Minister has racked up some expensive promises that need paying for, from lower tuition fee repayments to reversing tax rises and welfare cuts. And the electorate haven’t helped, cutting an already slim Tory majority down to the point where winning votes on anything controversial is all but impossible.

But when it comes to the top political task of this Budget, rebuilding Conservative support amongst the young, there is someone else causing problems, despite not being part of the official opposition, or indeed an MP, for the last two years. The Chancellor finds himself sandwiched between a do nothing Budget and Ed Balls.

At the centre of this challenge is the role of house building. Many Conservatives have rightly noted that housing is the single biggest issue driving concerns about intergenerational fairness. By a margin of 2 to 1 people now think that today’s young will have a worse life than their parents, and by a huge net margin of 63 per cent believe they won’t have the chance of owning a home their parents had.

It’s that stark discontent that Sajid Javid, the Secretary of State responsible for housing, is tapping into when he says housing is “the biggest barrier to social progress in our country today”. His aim is to build up to 300,000 additional homes in England a year – double the current level of 150,000.

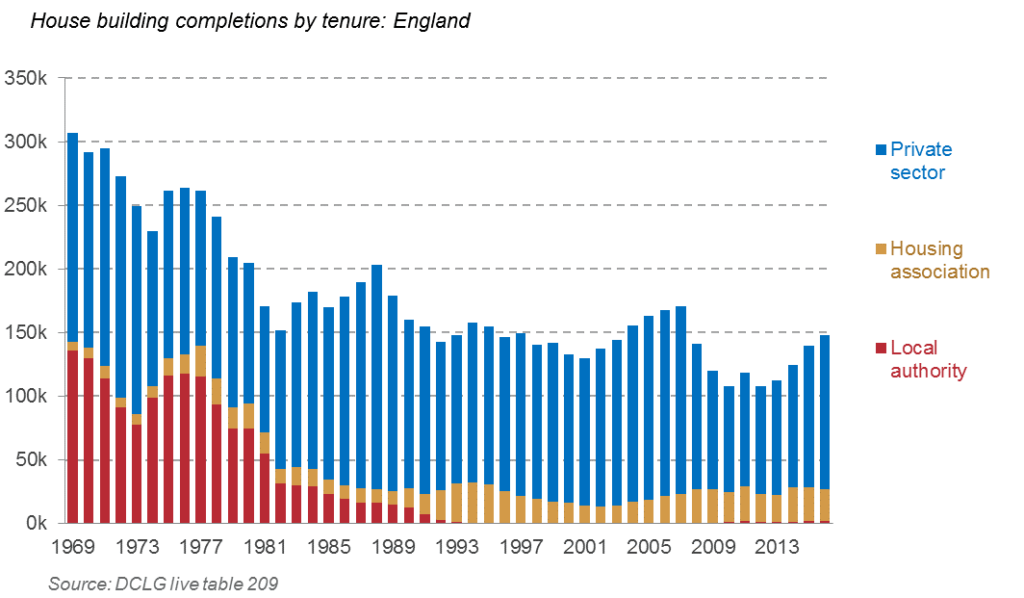

That is a huge increase, and one that simply won’t happen without large amounts of government spending. As is regularly noted, the big fall in house building since the 1970s has been driven largely by the state exiting the construction business.

But to date the government hasn’t followed that evidence through to its logical conclusion: that large state investment in house building is necessary if its targets are to be met. Instead it finds itself stuck announcing welcome but relatively incremental increases in spending, short term and unwelcome moves to prop up demand with Help to Buy and a focus on the process for how homes are bought and sold (which is no help to many of today’s young that have little chance of doing either). These are where you end up when you can’t address the problem head on.

Sajid Javid knows the answer to this problem, arguing recently “we can sensibly borrow more to invest in the infrastructure that leads to more housing, tak(ing) advantage of some of the record low interest rates that we have”.

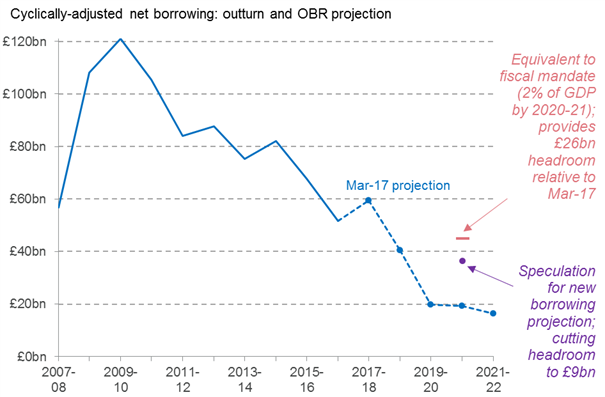

But, while he is right on the economics, he is wrong on the Budget arithmetic. Almost every economist agrees that an era of ultra-low interest rates is exactly the right time to invest to deliver lasting returns to the nation. But this plan falls foul of the constraints in the Chancellor’s main fiscal rule to “reduce cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing to below 2% of GDP by 2020-21”.

Two things are key about that rule. Firstly it treats all capital investment identically to current spending on day to day public services and social security – every extra penny the Chancellor spends on housing counts against it. Secondly the Chancellor is unlikely to have much wriggle room within it, given the speculation that a full two thirds of the £26bn headroom he has could be lost down the back of the OBR sofa because of more pessimistic forecasts.

So the Chancellor’s fiscal rule means he can’t do what Sajid Javid, or I suspect he, would like to do on housing. But why doesn’t he junk a rule that most economists think isn’t fit for purpose anyway? That’s where Ed Balls comes in.

Mr. Balls spent much of the 2010-15 Parliament arguing for capital and current spending to be treated differently in fiscal rules. Having spent years attacking this position Phillip Hammond can’t now adopt the Ed Balls approach, not least as it’s now the John McDonnell plan.

So here’s a constructive suggestion for getting round the impasse. If the Chancellor doesn’t want to separate out all capital spending, he can make an explicit exception for housing spend. It would open up important options in the forthcoming Budget, and isn’t a policy Labour has ever proposed.

Yes it’s a bit messy, and not what you’d call a first best policy option. But Britain needs housing built and we need our state fully involved in making that happen. And there is a case for treating it differently given that housing investment delivers quicker returns than, for example, rail spending.

There are many ways additional funding could be spent. The current £2.3bn available in the Housing Infrastructure Fund is expected to support the building of 100,000 homes over four years. The government could double the fund and double its impact, as well as reduce restrictions on its use by allowing Housing Associations to bid directly for cash.

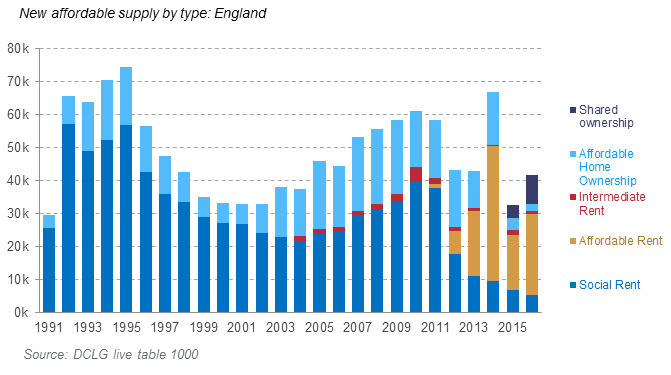

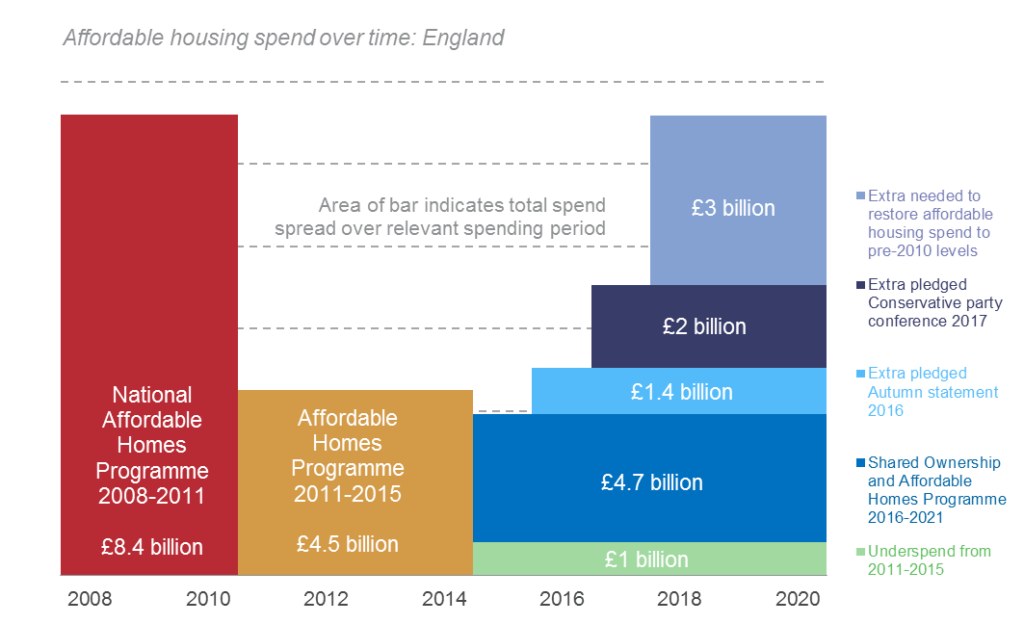

The Chancellor could increase funding for new affordable housing. The latest figures out today show that only 40,000 affordable homes were built last year, with the vast majority of these being for ‘affordable’ rent or shared ownership rather than genuine ‘social’ rent.

In terms of scale, an additional £3bn would reverse the cuts to affordable housing capital spending made since 2010 – and potentially deliver as many as 40,000 homes for social rent over the next three years at a time when over a million people are on local authority waiting lists.

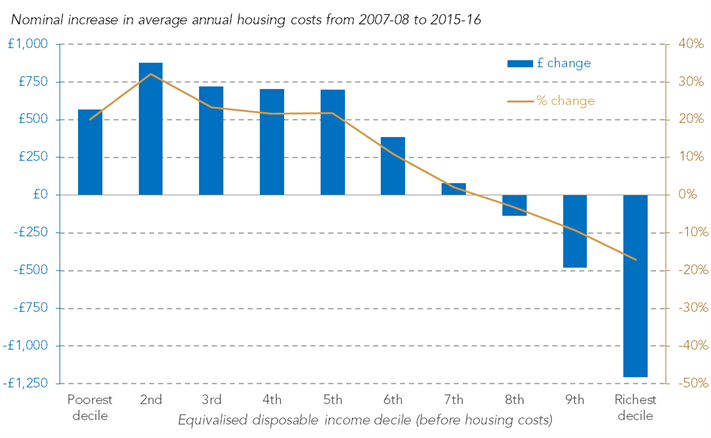

Such an approach would underpin a real One Nation Budget. Because on housing in Britain today everyone loses out. Better off households are most concerned about falling home ownership amongst their children, while poorer households have borne the brunt of increases in housing costs (having largely not benefited from the decade of near zero interest rates).

So in his upcoming Budget Philip Hammond doesn’t need to emulate Ed Balls to escape the straightjacket that holds him back on housing, and he certainly shouldn’t start dancing. He can exercise some creativity, set out that housing will rightly be centre stage for this government, and give himself the firepower to make that commitment a reality.